The Language of Symbols

Human beings have always sought ways to express emotions, ideals, and truths that transcend ordinary speech. Praise, devotion, longing, fear, and hope often find their purest expression not in plain words but in symbols. Across civilisations, mythologies and stories encode human experiences into symbolic forms: an animal, a weapon, a number, or even a colour becomes a vessel of meaning. Symbols are thus not decorative, but carriers of profound realities. Having seen the universal role of symbols, we now turn to their flowering within the Indian tradition, where symbolism becomes inseparable from the very identity of the deities.

Symbols in the Indian Tradition

In the Indian context, every Hindu deva or devī carries distinctive emblems: a dress, a weapon, a gesture (mudrā), or a companion.

Navarātra and the Symbolism of Nine

Among the many festivals that highlight divine symbolism, Navarātra holds a unique place. The very name means “nine nights”. The number nine itself is symbolic: it represents completeness, wholeness, and the culmination of cycles. In Indian numerology, nine is the highest single digit, signifying both fulfilment and renewal. Just as the number nine represents completeness, the triadic expression of Devī too encodes fullness. Now, let’s examine how the various forms ultimately converge on a single, supreme reality.

The Threefold Devī: Pārvatī, Lakṣmī, and Sarasvatī

At the heart of this symbolic universe stands the Devī in her many aspects. The Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa1 emphasises that these forms are but emanations of one supreme reality.

मेधासि देवि विदिताखिलशास्त्रसारा दुर्गासिदुर्गभवसागरनौरसङ्गा ।

श्रीः कैटभारिहृदयैककृताधिवासा गौरी त्वमेव शशिमौलिकृतप्रतिष्ठा ।।

medhāsi devi viditākhilaśāstrasārā

durgāsidurgabhavasāgaranaurasaṅgā ।

śrīḥ kaiṭabhārihṛdayaikakṛtādhivāsā gaurī tvameva

śaśimaulikṛtapratiṣṭhā ।।

(Mark. Pur. 81.11)

She is the Ādi-śakti, the primordial energy. She is sometimes called Ambikā, sometimes Mahādevī, Sarasvatī (मेधासि), Lakṣmī (श्रीः), and Durgā (गौरी). Thus, the original is one, but she appears as many, adapting her name and form according to the needs of the world and the devotion of the seeker.

Sometimes the triad is expressed as Durgā–Lakṣmī–Sarasvatī, other times as Ambikā (the universal mother) manifesting in multiple names. Each form carries its own weapons, vāhana-s, and ornaments, yet they are not separate entities.

In this way, symbolism in the Hindu tradition is not mere ornamentation; it is a profound and meaningful expression of spiritual significance. The vāhana, the festival, the number, the weapon, and the very name each is a coded language that points back to the original unity. With these symbols, one can enter a world where mythology, psychology, and spirituality meet, guiding the devotee toward inner transformation.

The most significant symbol is the vāhana (vehicle). The Sanskrit word vāhana literally means “that which carries or pulls.” Each Deva or Devī rides an animal or bird that is not chosen arbitrarily but represents the psychological and spiritual force that the deity commands.

The vāhana-s are so integral that Deva-s and Devī-s are rarely portrayed apart from them. Among these many layers of symbolic language, the vāhana emerges as a particularly vivid and dynamic symbol, one that deserves closer attention. It serves not merely as a mount but as an embodiment of the deity’s power, qualities, and cosmic role. In this study, special attention is given to the lion.

The lion constitutes the most prominent vāhana associated with the Devī, especially in her manifestations as Durgā or Mahīṣāsura-mardinī. Purāṇic narratives underscore this symbolism, noting that it was with the assistance of her lion vāhana that the Goddess was able to destroy the demon Mahīṣāsura.

सिंह, revered as the vāhana of Devī, is not only a Purāṇic image but also has deep roots in the Vedic imagination. The Ṛgveda employs lion imagery to symbolise strength and leadership (9.89.3), and Agni is figuratively associated with a lion, reflecting commanding and enduring qualities (1.95.5). Such references underscore the lion’s timeless symbolism of power, protection, and sovereignty, making it an apt vehicle for the supreme Mother.

In Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa Chapter 79, it is mentioned that the gods armed the Goddess with their divine weapons. The collective power of all the deities was invested in her radiant form for the battle with Mahīṣāsura.

हिमवान् वाहनं सिंहं रत्नानि विविधानि च ।

ददावशून्यं सुरया पानपात्रं धनाधिपः ।।

himavān vāhanaṃ siṃhaṃ ratnāni vividhāni ca ।

dadāvaśūnyaṃ surayā pānapātraṃ dhanādhipaḥ ।।

(Mark. Pur 79.29)

(This mentions that Himavān gave (to Devī) a lion as her vehicle, and various kinds of jewels.)

Being chief of forests, caves, and peaks, Himavān is naturally the source of mighty beasts. The lion, king of the forest, is fittingly in his domain. By offering the lion, Himavān acknowledges that the Devī is the only power who can command such a fierce creature.

Thereafter, in the battle narratives, other chapters during the battle with Mahīṣāsura, the Devī is repeatedly described as Siṃhavāhinī, riding a lion who actively assists her in slaying the Asura-s.

जयेति देवाश्च मुदा तामूचुः सिंहवाहिनीम् (श्लोक ७९.३४)

jayeti devāśca mudā tāmūcuḥ siṃhavāhinīm

पपातासुरसेनायां सिंहो देव्यास्तु वाहनः (८३.११)

papātāsurasenāyāṃ siṃho devyāstu vāhanaḥ

तेन केसरिणा देव्या वाहनेनातिकोपिना (८३.१५)

tena kesariṇā devyā vāhanenātikopinā

Again, during the Caṇḍa–Muṇḍa episode, she is depicted as seated smiling upon the lion atop a golden mountain peak, as

ददृशुस्ते ततो देवीमीषद्धासां व्यवस्थिताम् ।

सिंहस्योपरि शैलेन्द्रशृङ्गे महति काञ्चने ।। (८४.२)

dadṛśuste tato devīmīṣaddhāsāṃ vyavasthitām ।

siṃhasyopari śailendraśṛṅge mahati kāñcane ।।

In Śāradābhujaṅgaprayātāṣṭaka stotra by Śrī Śaṅkarācārya, Mṛgendra is mentioned in śloka 6 as a vāhana of the Goddess among many other vāhana-s, highlighting the lion’s continued prominence in devotional and literary traditions.

The Symbolism in the light of Amarakośa and Mṛgapakṣiśāstra.

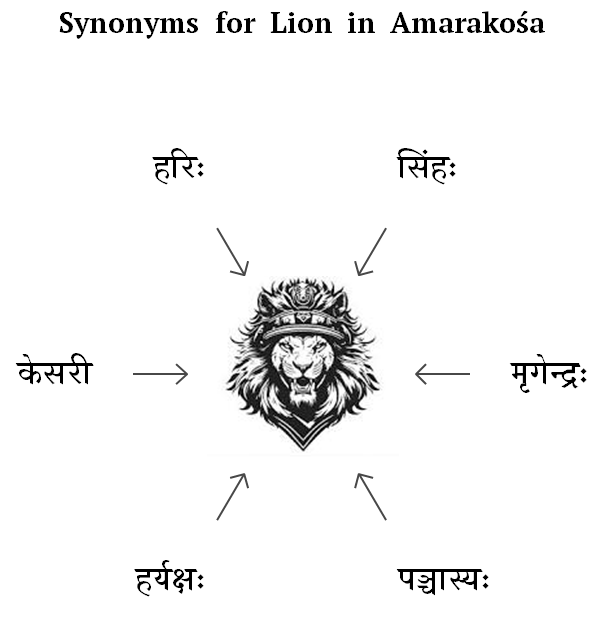

While the Purāṇic accounts emphasise the lion’s role in mythic battles, lexicons like the Amarakośa capture its essence through language itself, offering multiple names that encode its traits. The Amarakośa2 (Siṃhādivarga 2.5.1) enumerates multiple synonyms for the lion:

सिंहो मृगेन्द्रः पञ्चास्यो हर्यक्षः केसरी हरिः (Amarakośa 2.5.1)

siṃho mṛgendraḥ pañcāsyo haryakṣaḥ kesarī hariḥ

Although certain editions preserve additional readings, (कण्ठीरवो मृगरिपुर्मृगदृष्टिर्मृगाशनः ॥ २.५.१ पुण्डरीकः पञ्चनखचित्रकायमृगद्विषः । २.५.२

kaṇṭhīravo mṛgaripurmṛgadṛṣṭirmṛgāśanaḥ ॥ puṇḍarīkaḥ pañcanakhacitrakāyamṛgadviṣaḥ । ) the Ramāśramī commentary attests only the above six names.

The predominance of the lion as the Devī’s vehicle raises the question: why is the lion preferred over other animals? A possible explanation emerges from the Mṛgapakṣiśāstra3 of the Jain kavi Haṃsadeva (13th century CE).

Mṛgapakṣiśāstra catalogues various species of animals and birds alongside their distinctive traits. While the Mṛgapakṣiśāstra follows the Amarakośa in its taxonomy, it does not incorporate all the synonyms for every animal. This is evident from the following śloka-s of Mṛgapakṣiśāstra :

करोमि शास्त्रं बालानां हितायानेकपङ्क्तिकम् ।

निबद्धात्र मया श्रेणी सत्त्वानां तु पृथक् पृथक् ।। ३० ।।

karomi śāstraṃ bālānāṃ hitāyānekapaṅktikam ।

nibaddhātra mayā śreṇī sattvānāṃ tu pṛthak pṛthak ।।

(For the benefit of beginners, I compose this treatise in many verses. Here, I have arranged and presented the categories of beings separately.)

वर्णभेदः क्रियाभेदो जातिभेदस्ततः परम् ।

योषित्स्वरूपशैली च वयः कालश्च निश्चितः ।। ३२ ।।

varṇabhedaḥ kriyābhedo jātibhedastataḥ param ।

yoṣitsvarūpaśailī ca vayaḥ kālaśca niścitaḥ ।।

(These include distinctions of color, differences in actions, varieties of species, as well as the form and style of females, their age, and the time period is determined.)

गुणवर्णादिसंयोगैः सिंहाद्या बहुजातिकाः ।

मुख्यजात्युदिता एव वर्ण्यन्तेऽत्र मया क्रमात् ।। ३४ ।।

guṇavarṇādisaṃyogaiḥ siṃhādyā bahujātikāḥ ।

mukhyajātyuditā eva varṇyante’tra mayā kramāt ।।

(Through combinations of qualities, colors, and other factors, multiple kinds of species such as lions arise. Yet, in this work, I shall describe only their principal types, in proper sequence.)

To complement this linguistic mapping, the Mṛgapakṣiśāstra provides a more zoological description, grounding the lion’s symbolic identity in observed traits. An analysis of the lion vāhana-nāma-s in light of these zoological and symbolic classifications reveals that the selection of the lion as the goddess’s vāhana is deliberate. Each synonym emphasises characteristics as strength, majesty, courage, and auspiciousness that align with the symbolic role of the vāhana.

Thus, the usage of these terms reflects a confluence of linguistic tradition, natural observation, and symbolic association. The significance of each synonym common to the Amarakośa and Mṛgapakṣiśāstra can now be better understood by examining its etymology alongside zoological descriptions and symbolic interpretations of attributes of the Devī

1. Siṃha

This word is derived from the Sanskrit root हिसि (hiṃsāyām). The form undergoes वर्णविपर्यय (interchange of letters), resulting in सिंहः. In short, it denotes “the one who destroys,” i.e., the mighty killer.

According to the Mṛgapakṣiśāstra, the siṃha exhibits attributes such as swiftness like an arrow, a well-proportioned body, moderate claws, and a long, majestic tail, and they act with swift movements.

शरवद्वेगगतयो नातिदीर्घनखान्विताः ।

किञ्चिदायतगात्रश्च दीर्घवालधिभासुराः ॥ ६४ ॥

śaravadvegagatayo nātidīrghanakhānvitāḥ ।

kiñcidāyatagātraśca dīrghavāladhibhāsurāḥ ।।

क्षुत्काले अत्यन्त कोपाश्च ज्ञायन्ते त्वरितक्रमाः ॥ ६५ ॥

kṣutkāle atyanta kopāśca jñāyante tvaritakramāḥ

These physical characteristics symbolically correspond to the qualities of the goddess: Swiftness reflects her ability to act decisively against adharma. A well-developed, majestic body signifies authority and protective power. Moderate claws indicate controlled strength, highlighting the balance between ferocity and discipline. A long, attractive tail underscores elegance, dynamism, and a sense of grace.Thus, the lion serves as a dynamic extension of the goddess’s power, embodying strength, courage, and disciplined action.

2. Mṛgendra (King of Beasts)

The etymology of this term can be traced back to मृगाणामिन्द्रः, meaning “the chief of animals.”

The Mṛgapakṣiśāstra characterises mṛgendra as courageous, high-spirited, long-tusked, and fear-inducing, often seeking formidable challenges and eluding capture:

मृगेन्द्राः सन्ततं कोपहीना दीर्घसटा मताः ॥ ६८ ॥

mṛgendrāḥ santataṃ kopahīnā dīrghasaṭā matāḥ

गजान्वेषणशीलाश्चानल्पनादाः प्रकीर्तिताः ॥ ६९ ॥

gajānveṣaṇaśīlāścānalpanādāḥ prakīrtitāḥ

उत्तुङ्गाश्चोन्मदाः शूराः दीर्घदंष्ट्राः भयङ्कराः ॥ ७० ॥

uttuṅgāśconmadāḥ śūrāḥ dīrghadaṃṣṭrāḥ bhayaṅkarāḥ

सत्त्वानां भयदायकाः वागुरादिभिरग्राह्याः ॥ ७२ ॥

sattvānāṃ bhayadāyakāḥ vāgurādibhiragrāhyāḥ

These traits closely align with the symbolic attributes of the goddess: Courageous and high-spirited nature reflects her fearlessness and readiness to confront challenges. Long tusks and fierce demeanor signify the power to destroy evil and uphold Dharma. Elusiveness to capture mirrors the goddess’s dynamic, uncontrollable energy in overcoming adharma. Ability to instill fear underscores her protective role and authority over the unrighteous.

Mṛgendra, therefore, not only embodies physical prowess but also serves as a living symbol of the goddess’s formidable strength, courage, and divine authority.

3. Pañcāsya –

This is originating from the root ‘पचिँ विस्तारवचने’, interpreted as पञ्च विस्तीर्णमास्यं यस्य, “he whose mouth is greatly expanded.”The Mṛgapakṣiśāstra characterises Pañcāsya as Proud and exuberant, Fierce face with fangs, having terrifying roar:

मदान्विताः (७४), दंष्ट्रा करालवदनाः (७५), भयङ्करनिनादाश्च (७७)

madānvitāḥ (74), daṃṣṭrā karālavadanāḥ (75),

bhayaṅkaraninādāśca (77)

Pride and fierce demeanour reflect the goddess’s majesty, fearlessness, and authority. A terrifying roar symbolises her power to intimidate and destroy evil.

4. Haryakṣa

This term finds its origin as हरिणी पिङ्गले अक्षिणी यस्य, “the one whose eyes are tawny-brown, like those of a deer.”

The Mṛgapakṣiśāstra characterises Haryakṣa as Extremely fierce, Very strong, Long fangs and claws, Prideful, Extremely swift.

अधिकक्रूराः नितरां बलशालिनः

दीर्घदंष्ट्रा दीर्घनखा मदपूर्णा जवाधिकाः (७८)

adhikakrūrāḥ nitarāṃ balaśālinaḥ

dīrghadaṃṣṭrā dīrghanakhā madapūrṇā javādhikāḥ

Overwhelming power, fierce nature, and swift movement mirror the goddess’s martial prowess and decisiveness. Pride reflects supreme confidence, while long fangs and claws symbolise the ability to vanquish adharma.

5. Kesarī

The word comes from केसरोऽस्यास्ति or केसराः स्कन्धबालाः सन्ति अस्य, i.e., “he who possesses a mane, the tuft of hair on the shoulders / neck.”

Kesarī is described as possessing robust muscles, sturdy legs, claws eager to strike, a fierce fanged face, a reddish body, and remarkable swiftness:

दृढमांसा दृढपादाः करिभेदनलोलुपाः । गजझीङ्कारसङ्क्रुद्धा मृगयासक्तचेतसः ॥ ८४ ॥

dṛḍhamāṃsā dṛḍhapādāḥ karibhedanalolupāḥ ।

gajajhīṅkārasaṅkruddhā mṛgayāsaktacetasaḥ ॥

दंष्ट्राकरालवदना रक्तदेहा जवाधिकाः ॥ ८५ ॥

daṃṣṭrākarālavadanā raktadehā javādhikāḥ

These features symbolically reflect the goddess’s attributes: Robust muscles and sturdy legs indicate firmness, stability, and unshakable strength. Claws eager to strike and a fierce fanged face signify decisive power to vanquish evil. Enraged posture, likened to the trumpet of an elephant underscores wrath against adharma. The reddish body represents vitality, energy, and the fiery aspect of śakti.Devotion to the chase mirrors the goddess’s relentless pursuit of Dharma.

Kesarī thus epitomises the goddess’s martial prowess and protective energy, reinforcing her role as destroyer of evil and guardian of righteousness.

6. Hari

This is derived from the root हृञ् (हरणे), meaning “to take away, to remove.” Hence, हरति पापानि, “he who removes sins.”

The Mṛgapakṣiśāstra characterises Hari as Mild-tempered, Strong in youth, Deep, resonant roar, Calm by nature, yet courageous:

स्वल्पक्रोधाः (८७), यौवने बलपूर्णाश्च (८८),

svalpakrodhāḥ (87), yauvane balapūrṇāśca (88),

गम्भीरनिनादाः शान्तस्वभावाः शौर्येऽपि (९०)

gambhīraninādāḥ śāntasvabhāvāḥ śaurye’pi

Hari reflects controlled strength and strategic courage. A calm temperament denotes composure and wisdom, while a deep roar and courage indicate a latent power to protect devotees and uphold Dharma.

Beyond the six key synonyms, further traits of the lion enrich the Devī’s symbolism. As king of animals, the lion mirrors her sovereignty as Parāśakti and Śrīmahārājñī. Its fierce protection of cubs reflects her role as Śrīmātā, ever safeguarding her devotees. Just as the lion moves with its pride, the Devī is also surrounded by attendants, such as the Rāma-vāṇī and the Mātṛkā-s, highlighting her majesty and collective power. Thus, Siṃha-vāhana embodies not only strength but also sovereignty, maternal protection, and divinely ordered authority.

The Lion as Vāhana: A Consolidated View

The following table summarises the lion vāhana-nāma-s, presenting their key zoological traits alongside the corresponding symbolic attributes of the Goddess.

| Mṛgapakṣiśāstra | Key Traits (Physical & Temperament) | Symbolic Interpretation (Goddess Attributes) |

| Siṃha – शरवद्वेगगतयो नातिदीर्घनखान्विताः … दीर्घवालधिभासुराः (64–65) | Swift like an arrow; well-proportioned body; moderate claws; long tail; aggressive when hungry | Decisiveness; authority; protective power; controlled strength; elegance and dynamism; readiness to vanquish evil |

| Kesarī – दृढमांसा दृढपादाः … जवाधिकाः (84–85) | Strong muscles and legs; claws eager to strike; fierce fanged face; reddish body; extremely swift; devoted to the chase | Unshakable power; decisiveness; vitality and fiery śakti; relentless pursuit of Dharma; readiness to protect devotees |

| Mṛgendra – मृगेन्द्राः सन्ततं … वागुरादिभिरग्राह्याः (68–72) | Courageous and high-spirited; long tusks; fearsome; seeks challenges; difficult to capture; instills fear | Fearlessness; power to destroy evil; dynamic and uncontrollable energy; protective authority over the unrighteous |

| Pañcāsya – मदान्विताः, दंष्ट्रा करालवदनाः, भयङ्करनिनादाश्च (74–75) | Proud and exuberant; fierce face with fangs; terrifying roar | Majesty; fearlessness; authority; ability to intimidate and destroy evil |

| Haryakṣa – अधिकक्रूराः … जवाधिकाः (78) | Extremely fierce; very strong; long fangs and claws; prideful; extremely swift | Martial prowess; decisiveness; supreme confidence; ability to vanquish adharma |

| Hari – स्वल्पक्रोधाः … शौर्येऽपि (87–90) | Mild-tempered; strong in youth; deep, resonant roar; calm yet courageous | Controlled strength; composed wisdom; latent courage; ability to protect and uphold Dharma |

Practical applications for human development.

While these meanings illuminate the Devī’s iconography, they also invite reflection on how such symbolism can inspire human conduct and self-development in the present day. This symbolism also suggests practical applications for human development. The myths and iconography of the lion become a model for personal growth, helping devotees or learners incorporate these virtues into their behaviour. The table below presents these synonyms along with their etymologies, symbolic significance in Devī iconography, and practical applications for human development.

| Synonyms | Symbolism in Devī | Practical Application |

| सिंह (Siṃha) | Destructive force that annihilates adharma; mighty killer | Courage in adversity; ability to confront challenges decisively |

| मृगेन्द्र (Mṛgendra) | Sovereignty over all creatures; supreme authority | Leadership, responsible governance, and taking charge effectively |

| पञ्चास्य (Pañcāsya) | Boundless power; capacity to protect and consume evil | Ability to handle enormous responsibilities |

| हर्यक्ष (Haryakṣa) | Penetrating vision; insight into truth and falsehood | Clarity of perception; discernment in decision-making |

| केसरी (Kesarī) | Resplendent majesty; regal and radiant presence | Dignity, self-respect, and commanding presence |

| हरि (Hari) | Salvific compassion; remover of sins | Ability to overcome negativity; developing positivity |

Conclusion

The study of the lion as the Devī’s vāhana reveals a profound convergence of textual authority, linguistic tradition, and natural observation. The Purāṇic narratives emphasise the lion’s active role in the Goddess’s battles, the Amarakośa preserves multiple synonyms that encode its symbolic dimensions, and the Mṛgapakṣiśāstra enriches this picture with zoological descriptions of its traits. Taken together, these sources affirm that the lion is not an arbitrary mount but a carefully chosen emblem that embodies the Devī’s sovereignty, courage, and protective power.

Each synonym, Siṃha, Mṛgendra, Pañcāsya, Haryakṣa, Kesarī, and Hari, functions as a linguistic key to one aspect of her divine energy. Each signifies destructive decisiveness, supreme authority, boundless power, penetrating vision, regal majesty, salvific compassion. Beyond these six, the lion’s natural traits as its kingship of animals, its maternal protection of cubs, and its movement in a pride—further align with the Devī as Paraśakti, Śrīmātā, and Śrīmahārājñī.

Thus, when Devī is depicted as Siṃhavāhinī, it is not merely poetic imagery. Commentators like Sāyaṇācārya describe the lion as द्रुहस्पदे (difficult to access), highlighting its rare strength and inaccessibility (5.74.4). These timeless qualities, celebrated since the Vedic age, converge naturally in the Devī, who embodies supreme energy, motherly protection, and sovereign power.

Through these multiple dimensions, the Siṃha-vāhana becomes not only a symbolic companion but a living extension of the Goddess herself.

For the devotee and seeker, this symbolism carries practical significance. The lion becomes a model for cultivating courage in adversity, discernment in decision-making, dignity in conduct, and protection of the vulnerable. By meditating on the lion’s attributes, one is gently reminded of the Devī’s qualities, making her abstract śakti accessible and actionable in human life. Thus, the Siṃha-vāhana stands as more than mythic imagery: it is a bridge between nature and divinity, symbol and practice, memory and transformation. In this way, the lion continues to roar across texts, traditions, and hearts as a reminder of the Goddess’s enduring majesty and power.

Research – Dr. Leena R. Doshi

Guidance – Dr. Sowmya Krishnapur, Dr. CA. Viswanathan P, Dr. Venkatasubramanian P

Shortform – Mark. Pur. for Mārkaṇḍeya-Purāṇa

References

- Pargiter, F. Eden. The Mārkaṇḍeya-Purāṇa: Sanskrit Text, English Translation with Notes and Index of Verses. Edited by K. L. Shastri, Parimal Publications, 2004. ISBN 81-7110-223-7

- Amarkosha Ramashrami. Commentary by Bhanuji Dikshit, Edited by M. M. Pandit Sivadatta Dadhimatha, Revised by Pt. Vasudeva Lakshmana Panshikara. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthana, 2011. ISBN

- Haṃsadeva, Mrugapakshishastra, Edited by Maruti Chittampalli, Maharashtra Rajya Sahitya Sanskrutik Mandal, Mumbai, 1993

- Mṛgapakṣiśāstra https://archive.org/details/MrigaPakshiShastra/page/n166/mode/1up

- Vedic (ṚV) References to the Lion.

- Ṛgveda 9.89.3 Lion is used to symbolise strength and leadership.

https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/rig-veda-english-translation/d/doc838180.html - Ṛgveda 1.95.5 Agni figuratively associated with a lion, highlighting commanding and enduring qualities.

https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/rig-veda-english-translation/d/doc830020.html? - Ṛgveda 5.74.4 Sāyaṇācārya glosses lion as द्रुहस्पदे (difficult to access), emphasising rare strength and inaccessibility.

https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/rig-veda-english-translation/d/doc833564.html?

Courses

- To deepen your understanding of the lion as the goddess’s vāhana, you can enhance your Sanskrit vocabulary and pronunciation by following the Siṃhādi Varga of the Amarakośa. It’s an excellent resource for learners interested in linguistic and semantic aspects of Sanskrit.

https://www.sanskritfromhome.org/course-details/chant-amarakosha-secondkanda-part2simhadivarga-48888 - The following course offers a detailed, verse-by-verse English explanation of the Mahīṣāsuramardinī Stotra, a 21-verse hymn in praise of Goddess Mahīṣāsuramardinī. Traditionally chanted during Navarātri, it provides insights into the stotra’s poetic beauty and spiritual significance.

https://www.sanskritfromhome.org/course-details/mahishasura-mardini-stotram-40010